These remarks were delivered at the League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania and University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health 2022 Shale Gas & Public Health Conference on November 15, 2022--

Hi, everyone. It's so nice to be here with you, and thanks for the invitation and that really nice introduction.

I'm going to talk about some recent work that we've done looking at issues of environmental injustice in Pennsylvania related to wastewater disposal in the state.

I'll talk just a tiny bit about background on Marcellus [Shale gas], most people here probably don't need that, but just to get us started, and then I will talk a bit about distributive environmental injustice, the measure of deprivation that we use, community socioeconomic deprivation, and then results from this study.

We all know there have been these massive increases in natural gas production in the Pennsylvania Marcellus Shale over time, so this an important place to do this kind of work.

We also know that public interest in fracking in Pennsylvania mirrored this uptick in production, so people were Googling about it. That's what I'm showing here on the right.

Search interest in fracking in Pennsylvania peaked in 2014, but people were still interested in Googling this quite a bit.

In addition to this uptick in production, at the same time, we had a big increase in waste production.

So when wells are fracked, there are millions of gallons of water injected into the shale formation, and a lot of that comes back up as produced water.

So actually about 98% of waste production from fracked wells is in the form of produced water.

Where does this waste actually go? It has several different outlets.

So it can be reused to frack another well. It can go through wastewater treatment, although this is not happening very much anymore because we know that the wastewater can contain radioactive materials that conventional treatment plants can't deal with.

And then the third mechanism is putting it back on the earth, so land application, it can go into surface impoundments, it can be re-injected into disposal wells in the ground.

It can go to landfills, and it can be spread on roads.

I saw someone say in the chat that sometimes it is spread on crop fields. That seems to be the case, yes, in California, that sometimes wastewater is spread on fields where crops are grown.

I'm not aware of that happening in Pennsylvania, but it certainly is spread on land.

The focus for us was looking at land applied waste, because we thought these could potentially be routes through which human populations could be exposed to this waste.

If it's being reused in wells or put through treatment, we found that to be kind of less risky for human population. So this study really focused on land application mechanisms.

Yes, there were things that were scary about this huge uptick in fracking, potentials for environmental exposures and increase in waste production, but it did also generate a lot of money for the state of Pennsylvania.

Economic Benefits

So since 2012, companies drilling for gas in the Marcellus [Shale] are paying a per well fee that can compensate state and local communities for the burdens on public services and the environment, hopefully.

And so as of 2022, I was just checking these numbers, there's been about $2.2 billion put back into Pennsylvania communities from these fees.

In Pennsylvania there was also this big increase in local employment in oil and gas sector from 2007 to 2012.

These are some potential economic benefits of the drilling that's going on, but are these benefits evenly realized by people of the state of Pennsylvania?

Likely not.

Are There Disproportionate Exposures From Waste?

It's likely the case that some places have both socioeconomic disadvantage and disproportionate environmental exposures.

There are studies from prior states, such as Texas, that have actually shown a gradient of the proportion of people of color living in a block group and higher prevalence of wastewater injection wells in those places.

For example, this study led by Jill Johnston in Texas found that communities with over 80% people of color had 1.3 times the likelihood of having a wastewater treatment or a wastewater injection well in that community. [Read more here.]

People have done environmental justice studies in Pennsylvania related to the location of natural gas wells, and not actually found a gradient with socioeconomic status or issues with racial ethnic distribution.

No one, to our knowledge, had actually looked at where well waste was going, and so that's what we wanted to do here.

We were specifically asking the question, did waste disposal from oil and gas development occur disproportionately in socioeconomically vulnerable communities?

How were we measuring economic deprivation?

We were doing this at the county subdivision level, so townships and boroughs and cities, and we were doing this based on six census variables from the American Community Survey.

And these are things that we thought would correlate with deprivation, the proportion of people with less than a high school education, the proportion of people not in the labor force, the proportion living below the federal poverty threshold, the proportion of civilian unemployment, proportion of no car ownership, and proportion on public assistance.

So we sum those up and create one index where a higher score would mean the community is more deprived, a lower score would be less deprivation.

This is what it looked like across the county subdivisions overlaying the Marcellus Shale, which was our study area.

And so communities that are the least deprived are yellow, those with the highest levels of deprivation are this maroon brown color, so you can see the distribution there.

We then had access to the information on produced well waste from the EDWIN Database, which is the [DCNR] PA Geological Survey Exploration Development Well Information Network, a mouthful, so we like to call it EDWIN.

But we had data from 2005 to 2019, and so information here was at the well level. We knew how much liquid and solid waste was produced, how it was disposed, and also the location where that waste was disposed.

We were interested in well waste that stayed within Pennsylvania, because we wanted to learn about what Pennsylvanians were exposed to in terms of waste from this industry.

Where Is Waste Disposed?

A large portion of waste from Pennsylvania is actually taken out of state. A lot of it goes to Ohio for injection into wells there, but also a large portion remains in the state and so that's what we were focused on.

Like I said before, we wanted to look at the types of waste that were related to land applications, so things like disposal wells, landfills, and road spreading.

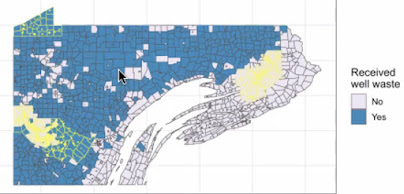

Here's a map of which county subdivisions did and did not receive waste between 2005 and 2019. [See map with this post.]

And so the periwinkle color means no well waste went to those communities, blue means well waste was received.

A huge portion of communities in Pennsylvania received some well waste during this time period.

The yellow outlines indicate the urban county subdivisions.

Because urban and rural areas can be very different in terms of their levels of deprivation and what it means, we stratify all our analyses by urban places and rural places in the state of Pennsylvania.

This is just a summary of the communities that were in our analysis. We have 404 urban communities and 1,400 rural communities.

You can see on average that this is broken down by communities that had drilled wells or didn't have drilled wells in these communities, so those with drilled wells in rural areas received the highest cumulative volume of waste, but actually urban areas were also receiving quite a bit of waste.

And rural areas had slightly higher levels of deprivation in this sample.

Some summaries on how much well waste was produced in the state over this time period.

There were 7 million tons of solid waste from wells and 19 million barrels [798,000,000 gallons] of liquid waste.

The volume of waste disposed of in the state of Pennsylvania actually increased over this time period. The highest volume of disposal occurred between 2017 and 2019.

Waste Disposed In Disadvantaged Communities

Here are the main results of our analysis, so let me walk you through this. We'll start on panel A, which are urban communities.

We saw that on average, as communities were more deprived, they had higher odds of receiving any well waste.

So this is just looking yes, no, the community received waste during the study period.

And so the most deprived communities had the highest odds of receiving waste in urban areas.

We also see something similar in rural areas, but the relationship is not as strong. But the most deprived rural areas did have higher odds of receiving well waste.

Now let's look at cumulative volume of well waste that these communities received.

We can see similar things.

So now focusing on our urban areas first, the most deprived urban communities, although there are only a couple of them out here, did receive the highest cumulative volume of waste.

In rural areas, the relationship with deprivation was stronger with volume of waste than it was with the binary yes, no-- received any waste variable.

So here in rural areas, we see the most deprived rural places received on average more cumulative well waste than other communities.

What did we see here? One, the volume of waste disposed of in Pennsylvania has increased over time.

More deprived communities were more likely to receive any well waste, as well as a larger cumulative volume of waste from 2005 to 2019 in Pennsylvania.

This is evidence of environmental injustice and is something that's been seen with toxic waste facilities previously and with wastewater injection wells, particularly in Texas as well as Ohio.

Finally, future oil and gas policy decisions need to start incorporating environmental justice considerations.

With that, I will say thank you.

Congrats to Wil Lieberman-Cribbin, the first author on this who just had the paper accepted in Environmental Justice, and to my co-authors, as well as NIEHS [National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences] for funding on this project.

Thank you very much.

Visit the League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania and University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health 2022 Shale Gas & Public Health Conference webpage for more information on the Conference.

Presentations from the Conference will be posted online in the coming weeks for on-demand viewing.

Joan Casey, PhD, Assistant Professor of Environmental Health Sciences, Columbia Mailman School of Public Health and received her doctoral degree from the Department of Environmental Health Sciences at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in 2014.

Dr. Casey is an environmental epidemiologist who focuses on environmental health, environmental justice, and sustainability.

Her research uses electronic health records and spatial statistics to study the relationship between emerging environmental exposures and population health.

She also considers vulnerable populations and the implications of health disparities, particularly in an era of climate change.

Dr. Casey investigates a range of exposures including unconventional natural gas and oil development, coal-fired power plants, wildfires, power outages, and concentrated animal feeding operations.

Related Articles This Week:

-- What Can We Expect From Gov. Shapiro, Lt. Gov. Davis On Environmental, Energy Issues? [PaEN]

-- DEP Assesses $200,000 In Penalties For Drilling Wastewater Spills By CNX In Greene County [PaEN]

-- Center For Coalfield Justice Holds First Water Distribution Day Nov. 19 To Help Provide Families Drinking Water In Greene County Following Alleged ‘Frack-Out’ At Natural Gas Well Site In June [PaEN]

-- Post-Gazette: Efforts To Stop A Natural Gas Leak For The Last 12 Days At A Cambria County Underground Gas Storage Area Have Failed, Gas Is Again Escaping [PaEN]

-- Washington County Family Lawsuit Alleges Shale Gas Company Violated The Terms Of Their Lease By Endangering Their Health, Contaminating Their Water Supply And Not Protecting Their Land [PaEN]

-- Shale Gas & Public Health Conference: We've Got Enough Compelling Evidence To Enact Health Protective Policies For Families Now - By Edward C. Ketyer, M.D., President, Physicians for Social Responsibility Pennsylvania [PaEN]

-- Shale Gas & Public Health Conference: When It Started, It Was Kind Of Nice, But What Happened Afterwards Really Kind Of Devastated Our Community - By Rev. Wesley Silva, former Council President Marianna Borough, Washington County [PaEN]

-- Shale Gas & Public Health Conference: Living Near Oil & Gas Facilities Means Higher Health Risks, The Closer You Live, The Higher The Risk - By Nicole Deziel PhD MHS, Associate Professor of Epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health [PaEN]

-- Observer-Reporter: Ongoing Water Donation Drive Helping Dozens Of Greene County Families Who Haven’t Had Clean Drinking Water Since June Following Alleged ‘Frack-Out’ At Natural Gas Well Site [PaEN]

-- YaleEnvironment360 - Jon Hurdle: As Evidence Mounts, New Concerns About Fracking And Health

-- Pittsburgh Business Times: Natural Gas Drilling Ban Supporters See Wider Effort In Allegheny County Towns

-- Young Evangelicals For Climate Action Celebrates Stronger Proposed EPA Oil & Gas Methane Standard [PaEN]

-- Environmental Health Project Calls Proposed EPA Oil & Gas Methane Emissions Rule Good First Step [PaEN]

-- IRRC Approves Final VOC/Methane Emission Limits On Conventional Oil & Gas Wells - Federal Highway Funds Still At Risk; And First State MCL For PFOS/PFOA [PaEN]

Related Articles - Health & Environmental Impacts:

-- Senate Hearing: Body Of Evidence Is 'Large, Growing,’ ‘Consistent’ And 'Compelling' That Shale Gas Development Is Having A Negative Impact On Public Health; PA Must Act [PaEN]

-- Penn State Study: Potential Pollution Caused By Road Dumping Conventional Oil & Gas Wastewater Makes It Unsuitable For A Dust Suppressant, Washes Right Off The Road Into The Ditch [PaEN]

-- On-Site Conventional Oil & Gas Drilling Waste Disposal Plans Making Hundreds Of Drilling Sites Waste Dumps [PaEN]

-- Conventional Oil & Gas Drillers Dispose Of Drill Cuttings By ‘Dusting’ - Blowing Them On The Ground, And In The Air Around Drill Sites [PaEN]

-- Creating New Brownfields: Oil & Gas Well Drillers Notified DEP They Are Cleaning Up Soil & Water Contaminated With Chemicals Harmful To Human Health, Aquatic Life At 272 Locations In PA [PaEN]

-- Gov. Wolf, Senate, House Republicans Again Fail To Hold Conventional Oil & Gas Drillers Accountable For Protecting The Environment, Taxpayers On Hook For Billions [PaEN]

-- Conventional Oil & Gas Drillers Reported Spreading 977,671 Gallons Of Untreated Drilling Wastewater On PA Roads In 2021 [PaEN]

-- NO SPECIAL PROTECTION: The Exceptional Value Loyalsock Creek In Lycoming County Is Dammed And Damned - Video Dispatch From The Loyalsock - By Barb Jarmoska, Keep It Wild PA [PaEN]

-- Rare Eastern Hellbender Habitat In Loyalsock Creek, Lycoming County Harmed By Sediment Plumes From Pipeline Crossings, Shale Gas Drilling Water Withdrawal Construction Projects [PaEN]

Impact Of Oil & Gas Industry:

-- PA Environment Digest Articles On Health & Environmental Impacts Of Oil & Gas Industry

[Posted: November 17, 2022] PA Environment Digest

No comments:

Post a Comment