These remarks were delivered at the League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania and University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health 2022 Shale Gas & Public Health Conference on November 15, 2022--

It's my great pleasure to be here today. I would like to thank the League of Women Voters, in particular Heather Harr, as well as the Technical Organizing Committee for the invitation to speak today and to reflect on the last decade of health-related research on unconventional oil and gas development, or UOGD.

When I first entered this field, which was not quite a decade ago, it was about eight years ago, there were already many excellent papers such as this one, the seminal paper I'm highlighting here.

A lot of the papers talked about the potential hazards, the potential exposures, the potential health risks from unconventional oil and gas development.

And this was informed by a lot of data and evidence from the conventional oil and gas drilling industry, as well as some early research into UOGD.

But from my perspective, when I first started doing research into this area, the UOGD specific health research was kind of one big question mark.

So in today's talk, I'd like to kind of walk through what we have learned over the past decade, and what can we say now with a little more certainty.

Can we move away from this idea of potential risks and hazards and draw some firmer conclusions from all this evidence?

Over this past decade, there's been a rapid increase in unconventional oil and gas development in the United States.

You've probably seen graphs like these before showing an approximate eightfold increase in production of shale gas over the past 10 years or so, with millions of people living near an unconventional oil and gas well, having their drinking water source near an unconventional oil and gas well, with about 160,000 active wells currently.

This has all been accompanied by high community concern.

I'd like to acknowledge that there are many possible, or while there were many potential stressors identified early on, there's also been a decade of a tremendous amount of research on the emissions, the exposures of these hazards.

I don't have time to go into that today in this 20-minute talk, I'll be focusing on the health research.

But I did want to acknowledge that there is evidence for all of these hazards to be associated with unconventional oil and gas development.

Now, we don't have a good handle, necessarily, on the intensity of the emissions, the frequency, the duration. Certainly we may not see all of these at every well all the time. So those are still some of the unanswered questions.

But all of these have been documented in communities in measurements from unconventional oil and gas development well sites, so that this compliments some of the activity with the health research.

The questions I'd like to try to walk through with you today are, what have we learned from the body of unconventional oil and gas related health research, what are the gaps, and offer some of my own reflections on relevance to policy and future directions for this field.

This graph gives an overview of all the tremendous amount of research that has occurred over the past approximate decade. I showed the other time plot of the rapid expansion of unconventional oil and gas development.

As researchers, there's kind of been a delay as we sort of lag behind the growth in the industry to try to evaluate the health impacts.

It takes a lot of time to do really good research. There's been limited funding available.

But despite that, there's been a large body of evidence over time with more studies coming out each month on this topic.

Many of you may be familiar with the fact that the most commonly studied outcome is perinatal outcomes with the majority of studies looking at things like low birth weight, preterm birth, birth defects, with the other health outcomes having kind of small but growing numbers of studies tackling these other health outcomes.

So I do think this is an area where we could continue to investigate. And there are also some outcomes that aren't covered by these plots that are underrepresented.

For example, adult cancers. We haven't had sufficient latency really to study those yet.

So there are still some health outcomes that are understudied. Let's look at where these studies have been conducted.

The most common state or location for this research has been here in Pennsylvania, with studies occurring though in several other locations.

I should say this is based on recent reviews of epidemiologic studies, so health studies specifically, that have looked at unconventional oil and gas development or both conventional and unconventional oil and gas development.

And if you set slightly different criteria, you might get slightly different numbers.

But these are my numbers based on some recent reviews that I've worked on as well as some recent searches.

Although Pennsylvania has, most of the studies are here in the Marcellus Shale area, there have been some recent studies looking at the entire country, which I think is an important new development in this field.

Even though there certainly is heterogeneity in the operations from state to state, there's a lot of similarities in terms of the hazards released.

And there's no reason to think that results from Pennsylvania don't bear relevance to populations in California and vice versa.

I know policymakers can give more weight to things that occur or studies that are conducted in their own states, but all of these studies are important and can provide relevance to different locations.

Increased Health Risks

So my takeaways from the literature are that most of these studies do find associations between living near unconventional oil and gas development and increased health risks, the overwhelming majority.

As we presented, the adverse perinatal health outcomes are the most commonly studied endpoints with the strongest evidence.

Although not every study finds exactly the same thing, the results are very consistent. They're all pointing in similar directions.

So similar findings across multiple states, multiple time periods, multiple populations, mostly pointing to increased health risks, all provides coherence and confidence to this body of evidence.

Then I also want to point out that all of these studies so far have used some form of proximity-based measures to assign exposures. So something similar to how close you live to an unconventional oil and gas well. Let's dig into these a little bit deeper.

As I mentioned, can we say anything more than perinatal outcomes are the most well studied health outcome? Can we draw some conclusions?

I recently served on a panel with many of the speakers at this conference where we reviewed the evidence for perinatal outcomes and other health studies.

We applied these criteria called the Bradford Hill criteria, which are used to assess epidemiologic studies and the weight of evidence to determine if there's certainty about the body of evidence and the associations they're studying.

I've highlighted some of these criteria here, and I'll just briefly walk through some of them with you. For example, one of the criteria is the strength of the association.

Were the odds ratios or the risk ratios in the studies similar to what we would expect given the potential hazards?

We found this to be met, that effect estimates were similar to air pollution or PM2.5, which have also been associated with perinatal outcomes.

These are established hazards.

Consistency, as I mentioned, there are similar results in similar populations for studies that are using different methods, different time periods. That kind of consistency really lends confidence to the overall body of evidence.

Specificity means, could there be some other explanation for these associations?

Well, most of the studies were very well designed and they considered numerous other individual level, or area level, community level confounders, like other sources of pollution. Or they used statistical methods like how we had speakers here talk about the difference and difference design.

So both of these types of approaches, either these statistical models or inclusion of confounders, really try to isolate and control for other possible explanatory variables.

Temporality means, did the exposure come before the health outcome? Almost all the studies included wells that were active before the baby was born. It wouldn't make sense scientifically to count a well that was drilled after birth if we're looking at birth outcomes.

Many studies also saw that with higher exposure potential, there was a greater risk. This is also plausible based on other research about these hazards that are known to be emitted from oil and gas sites.

Based on all of this, we concluded in this public letter that the totality of epidemiologic evidence provides a high level of certainty that exposure to oil and gas, this was a little broader, including conventional and unconventional, causes significant increase of risk of poor birth outcomes.

So this is one way we can evaluate the body of evidence so far.

Living Closer Means Higher Health Risks

Okay, and I wanted to talk a little bit now about exposures.

As I mentioned, most of the studies use some sort of a proximity-based exposure model. Some of them are what I call the aggregate proximity metrics.

So they may count how many wells are within a certain distance from a home, or look at the closest well to someone's home.

So these aren't specific to air pollution or stress, they're just considering the oil and gas well as a whole entity. This is very useful because one gap is, we still don't really know what the dominant stressor or hazard is.

Maybe it's not one thing. Maybe it's a combination of things. So these types of proximity to oil and gas well metrics, you don't need to figure out which is the most important hazard. It just kind of treats them all collectively.

This is also really easy to interpret and explain to policymakers.

Living closer means you have higher health risks than living farther away. The disadvantage is that it doesn't tell you about the important hazards or etiologic agents.

Also, it doesn't account for direction of dispersion of pollutants.

In the health studies that have been done so far, there's been tremendous growth in the development of specific models or metrics, including in our group we've been looking into including the direction of the water flows.

We've applied new metrics that only count oil and gas wells that are up gradient from a drinking water well.

Other studies have taken into account the wind direction so that you're not counting oil and gas wells that are downwind from a home.

Other studies have looked at earthquakes, or flaring, or other specific stressors, which is also really valuable because this can add more specificity and precision, and reduce error and misclassification in our studies.

But it also can be more computationally intensive, require more data, and then it starts to get a little less interpretable, or it's not as easy to translate to policy.

A question that often comes up is, "Why aren't epidemiologists taking measurements?"

Measurements are extremely valuable for providing objective and quantitative values for specific chemicals or hazards. However, this is very difficult to do in large studies where some of these studies have had a million births.

Also, as I said, we still don't know exactly what is the dominant hazard. If you think about trying to measure everything in the air, in the water, and the noise, and the stress, and light at night, it becomes just very challenging to really do a very comprehensive assessment.

And there isn't a lot of data, publicly available data, where a lot of the drilling is occurring.

We don't have as many air monitors in rural areas which are less populated. We don't routinely monitor people with private drinking water wells because it's not regulated by our federal government.

Also, you can go out and collect the best measurements now, but if you're interested in what children who have cancer now were exposed to five years ago, collecting measurements now is not going to be helpful for that.

So that's something that hasn't been done yet in the health studies. So how has all of this research been informing policy?

Hierarchy Of Controls

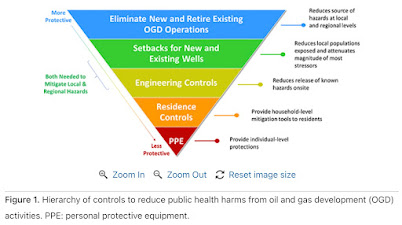

I wrote this commentary with, again, many of the speakers here at the meeting. We really tried to think about what is the evidence telling us and how can this inform different policies to protect public health from unconventional oil and gas development?

We applied this hierarchy of controls, this inverted pyramid, which is commonly used in the occupational setting.

What it depicts, first of all, is that when we want to protect public health we usually want to have lots of layers of protections. We want to have some redundancy and not just have one level or another. And the higher you go on the pyramid, the more protective the solution is.

So for example, because a lot of the health studies have looked at proximity, they've been very useful for informing policies like setbacks. Or they could be if states are considering to update their setback policies.

This can be effective in reducing local populations' exposure because we know that the risk and exposures attenuate with distance. However, this is not sufficient to reduce risk because it doesn't necessarily capture the pollutants.

They're still being released, but we're just putting it farther away from people. So it can still contribute to greenhouse gas releases and emissions, regional air quality issues.

We could add another layer of say engineering controls, which are controls that capture emissions of pollutants right at the source.

So things that could capture methane and VOCs, or have noise barriers, or things like that.

But this requires knowing what the hazards of interest or importance are, and we still need some more information on that. Also, there are no controls that could capture all the complex stressors that could be emitted from different sites.

Of course, reducing drilling would be most protective. That's why it sits at the top, because you're not releasing pollutants, you're not just moving things farther away. You're controlling things right at the source by reducing the source.

And just another thought, the field of environmental health is moving towards this idea of planetary health.

So something else I've been thinking about is while setbacks can be very valuable and communities, and community groups may really want these types of protections, if we move oil and gas wells farther away from people, where are we putting them?

And we may want to think about how if we put things far from people, then we may be encroaching upon animals and their habitats, interfering with migratory patterns.

We tend to do things kind of siloed.

Where here we're talking about people at this meeting, there may be other meetings talking about wildlife, and the land, and plants. But there actually is a robust body of literature also documenting impacts to other life forms and the land.

Then finally, as Dr. Wenzel mentioned in her remarks, thinking ahead there's still a lot of other infrastructure associated with the oil and gas industry, including these plastics and ethane cracker plants.

And there's very little data on the health impacts of some of these other pieces of the more downstream infrastructure.

So I think that is also an important gap and direction for future research.

Conclusion

To summarize, although there are some health outcomes that remain understudied, the body of evidence does support that people who live closer to unconventional oil and gas development experience greater health impacts compared to those who live farther away.

And the body of evidence for perinatal outcomes in particular provides a high level of uncertainty about that association.

Exposure assessments are becoming more specific and detailed, and these more robust methods can help reduce exposure misclassification and inform effective mitigation strategies.

I'd like to point out that trying to figure out the dominant exposure or trying to study adult cancer, I think these are valuable, important endeavors.

But these could take another decade or two decades to sort out, and that we don't need to wait to fill all these gaps to start implementing public health protections that can be done concurrently.

With that, I'd like to thank my many collaborators, and co-authors, and funding for some of my research that I presented. Thank you.

Visit the League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania and University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health 2022 Shale Gas & Public Health Conference webpage for more information on the Conference.

Presentations from the Conference will be posted online in the coming weeks for on-demand viewing.

Dr. Nicole Deziel is a tenured Associate Professor in Environmental Health Sciences at the Yale School of Public Health and a member of the Yale Cancer Center and Yale Center for Perinatal, Pediatric and Environmental Epidemiology.

Her research involves applying statistical models, biomonitoring techniques, and environmental measurements to provide comprehensive and quantitative assessments of exposure to combinations of traditional and emerging environmental contaminants.

Dr. Deziel has been a leader in evaluating the exposures, health, and environmental justice impacts of unconventional oil and gas development. She directed an inter-disciplinary team of investigators on a project entitled “Drinking water vulnerability and neonatal health outcomes in relation to oil and gas production in the Appalachian Basin,” which evaluated potential impacts to drinking water and children’s health outcomes from hydraulic fracturing.

She has published over 20 research articles, reviews, and commentaries related to fracking to date. Dr. Deziel serves as Executive Editor for the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology and is on the Editorial Board of Environment International.

Related Articles This Week:

-- What Can We Expect From Gov. Shapiro, Lt. Gov. Davis On Environmental, Energy Issues? [PaEN]

-- DEP Assesses $200,000 In Penalties For Drilling Wastewater Spills By CNX In Greene County [PaEN]

-- Washington County Family Lawsuit Alleges Shale Gas Company Violated The Terms Of Their Lease By Endangering Their Health, Contaminating Their Water Supply And Not Protecting Their Land [PaEN]

-- Center For Coalfield Justice Holds First Water Distribution Day Nov. 19 To Help Provide Families Drinking Water In Greene County Following Alleged ‘Frack-Out’ At Natural Gas Well Site In June [PaEN]

-- Post-Gazette: Efforts To Stop A Natural Gas Leak For The Last 12 Days At A Cambria County Underground Gas Storage Area Have Failed, Gas Is Again Escaping [PaEN]

-- Shale Gas & Public Health Conference: We've Got Enough Compelling Evidence To Enact Health Protective Policies For Families Now - By Edward C. Ketyer, M.D., President, Physicians for Social Responsibility Pennsylvania [PaEN]

-- Shale Gas & Public Health Conference: When It Started, It Was Kind Of Nice, But What Happened Afterwards Really Kind Of Devastated Our Community - By Rev. Wesley Silva, former Council President Marianna Borough, Washington County [PaEN]

-- Shale Gas & Public Health Conference: Economically, Socially Deprived Areas In PA Have A Much Greater Chance Of Having Oil & Gas Waste Disposed In Their Communities - By Joan Casey, PhD, Assistant Professor of Environmental Health Sciences, Columbia Mailman School of Public Health [PaEN]

-- YaleEnvironment360 - Jon Hurdle: As Evidence Mounts, New Concerns About Fracking And Health

-- Pittsburgh Business Times: Natural Gas Drilling Ban Supporters See Wider Effort In Allegheny County Towns

-- Young Evangelicals For Climate Action Celebrates Stronger Proposed EPA Oil & Gas Methane Standard [PaEN]

-- Environmental Health Project Calls Proposed EPA Oil & Gas Methane Emissions Rule Good First Step [PaEN]

-- IRRC Approves Final VOC/Methane Emission Limits On Conventional Oil & Gas Wells - Federal Highway Funds Still At Risk; And First State MCL For PFOS/PFOA [PaEN]

Related Articles - Health & Environmental Impacts:

-- Senate Hearing: Body Of Evidence Is 'Large, Growing,’ ‘Consistent’ And 'Compelling' That Shale Gas Development Is Having A Negative Impact On Public Health; PA Must Act [PaEN]

-- Penn State Study: Potential Pollution Caused By Road Dumping Conventional Oil & Gas Wastewater Makes It Unsuitable For A Dust Suppressant, Washes Right Off The Road Into The Ditch [PaEN]

-- On-Site Conventional Oil & Gas Drilling Waste Disposal Plans Making Hundreds Of Drilling Sites Waste Dumps [PaEN]

-- Conventional Oil & Gas Drillers Dispose Of Drill Cuttings By ‘Dusting’ - Blowing Them On The Ground, And In The Air Around Drill Sites [PaEN]

-- Creating New Brownfields: Oil & Gas Well Drillers Notified DEP They Are Cleaning Up Soil & Water Contaminated With Chemicals Harmful To Human Health, Aquatic Life At 272 Locations In PA [PaEN]

-- Gov. Wolf, Senate, House Republicans Again Fail To Hold Conventional Oil & Gas Drillers Accountable For Protecting The Environment, Taxpayers On Hook For Billions [PaEN]

-- Conventional Oil & Gas Drillers Reported Spreading 977,671 Gallons Of Untreated Drilling Wastewater On PA Roads In 2021 [PaEN]

-- NO SPECIAL PROTECTION: The Exceptional Value Loyalsock Creek In Lycoming County Is Dammed And Damned - Video Dispatch From The Loyalsock - By Barb Jarmoska, Keep It Wild PA [PaEN]

-- Rare Eastern Hellbender Habitat In Loyalsock Creek, Lycoming County Harmed By Sediment Plumes From Pipeline Crossings, Shale Gas Drilling Water Withdrawal Construction Projects [PaEN]

Impact Of Oil & Gas Industry:

-- PA Environment Digest Articles On Health & Environmental Impacts Of Oil & Gas Industry

[Posted: November 17, 2022] PA Environment Digest

No comments:

Post a Comment